Dr. David Grimes performed his first abortion in 1972 as a medical student at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Five years before, North Carolina had joined Colorado and California in becoming the first states to legalize abortions in a few select scenarios: rape, incest, physical or mental defects in the child, and threats to the health or life of the mother.

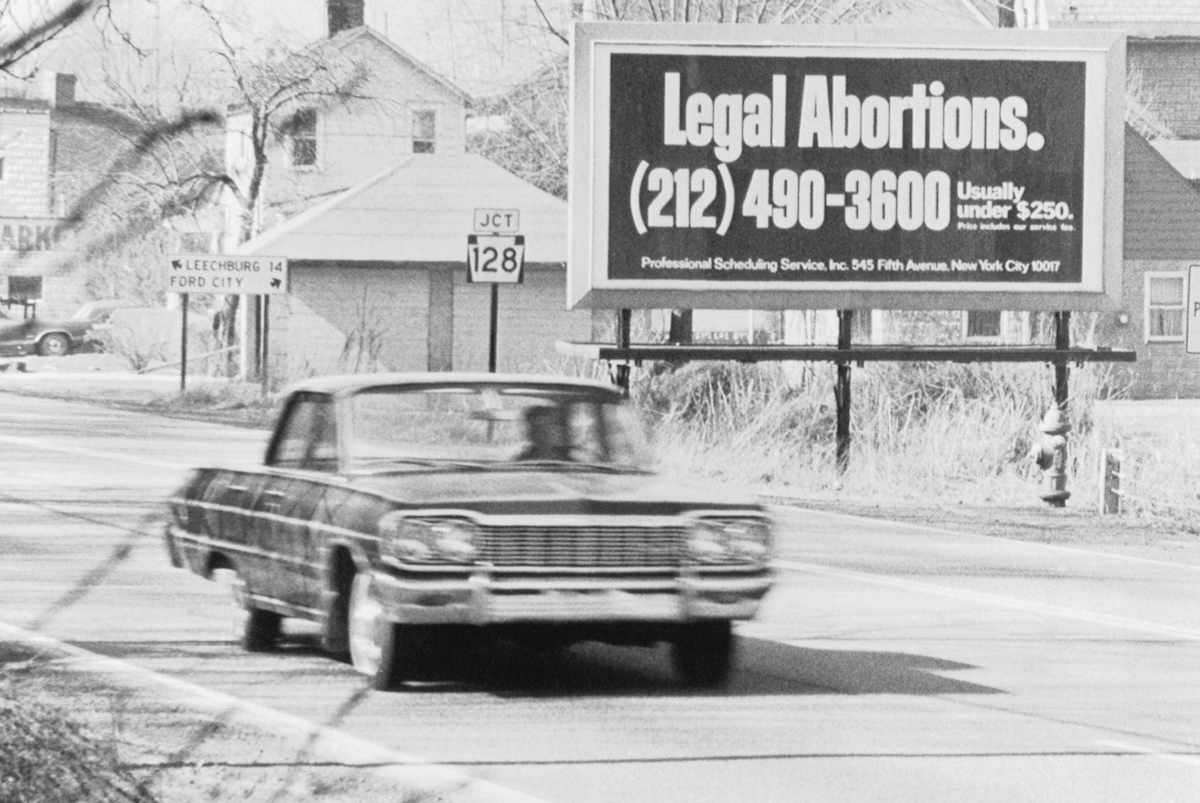

The Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade made abortion legal, upon the mother’s request, across the nation. The decision came shortly before Grimes graduated from medical school, and he would go on to perform the procedure many times in his 42-year OB-GYN career. Now retired, he is an author of Every Third Woman in America: How Legal Abortion Transformed Our Nation.

These days, the number of abortion clinics has been dwindling at a record pace, according to a Bloomberg Business report, as a result of better access to birth control as well as increasingly strict regulations on the procedure. Some states are down to just one, including Kentucky, where activists announced this week their goal of shutting down the state’s last clinic. TIME spoke with Grimes about his experience as an abortion provider and the differences before and after Roe v. Wade.

What made you want to get into this area of women’s health?

North Carolina was ahead of the curve. It was quite a progressive state back then, and North Carolina laws were liberalized several years before Roe v. Wade. So I became interested as a both social issue as well as a medical issue. And I began providing abortions as a fourth-year medical student in 1972 and continued throughout my career. It was very apparent to anybody with an open eye and an open mind that this is just a fundamental part of women’s health care and couldn’t just be avoided.

What was the medical atmosphere nationally regarding abortion prior to its legalization, when the procedure was often performed underground?

Frustration would be the best word, and physicians just could not accept the carnage that we witnessed. It’s important to remember that there were two groups that fundamentally drove the legislative process in the 1960s and early 1970s toward liberalization. One was the clergy, because they had to deal with these women in crisis and oftentimes would assist with referrals to safe providers, and then physicians [who] were left to deal with the women who were damaged or killed by [illegal] abortion.

Did you ever see or treat women who were in that situation?

Yes, I did, as well as seeing them internationally. I describe two cases [in Every Third Woman] that I still remember vividly decades later. One was a woman who came in with a temperature of 106, 107 degrees. I’ve never seen anyone that hot before except for with heat stroke. On examination, it turned out she had a red rubber catheter protruding from her cervix that had been put in place by a dietician in the next town over. This is a standard, old illegal abortion technique, quite effective but also quite dangerous. We saved her life.

[In the second instance] I got called down to the emergency department to a see a young woman, a coed from on campus, who was in septic shock. She had virtually no blood pressure. And on examination, I found a dead fetal foot protruding through her cervix at about 17 weeks of pregnancy and [under] suspicious circumstances. We saved her life, as well.

In the early 1980s, I was working at the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] in Atlanta and traveled internationally. I made several trips to Bangladesh and had the chance to visit a number of hospitals, and I would see wards filled with women dying needlessly from abortion. All we had to offer them was oral antibiotics [because] they didn’t have the surgical techniques to enter the uterus. So I saw entire wards of doomed women.

For a young physician to encounter those kinds of horrors changes you irrevocably, and you will make a vow to yourself, “Never, never will I allow that to any woman I could care for.”

What are the major differences in being an abortion provider today versus before Roe v. Wade?

The technology has moved very quickly to provide safer, simpler, cheaper, better services for women — plus, the opening of medical abortion, which has been an important, new chapter for American women. For many, many years after the legalization of abortion, we had surgical abortion and nothing else, so if you wanted an abortion, you had an operation and didn’t have any other choice. Choice is important.

And [the] actual cost of abortion has dropped precipitously over the years. It’d be very hard to think of any other dental or medical procedure that’s dropped in price [as] dramatically over the last the last 30 or 40 years.

What are your thoughts on the decrease in the number of abortion clinics in certain states?

What it does is to hurt the women involved — and society more broadly because it raises the cost, first of all. It’s going to be expensive. It also delays abortions. It takes several weeks to scrounge up the money or arrange for transportation. And one of the early lessons we learned back in the 1970s was: When it comes to abortion, the earlier, the better — that is, it’s safer, more comfortable and more convenient. Any delay — whether it be administrative, financial, regulatory — serves to increase the risk and expense to the woman, and that violates the fundamental principle of beneficence. Everything we do to patients and for patients should be in their best interest.

Do you think they’ll ever be a time when a woman in the U.S. won’t legally be able to obtain an abortion?

No, I don’t think we’ll see that. [But] these efforts to limit access can have the same effect.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com