Shoko Asahara admired Hitler, so it was perhaps fitting that when the cult leader set out to terrorize Tokyo, he used a nerve gas called sarin, first developed in Nazi Germany. The Nazis had never used the highly potent chemical, which they’d originally produced as a pesticide, against Allied forces during World War II. Asahara is one of the few people in history to have unleashed it on the public.

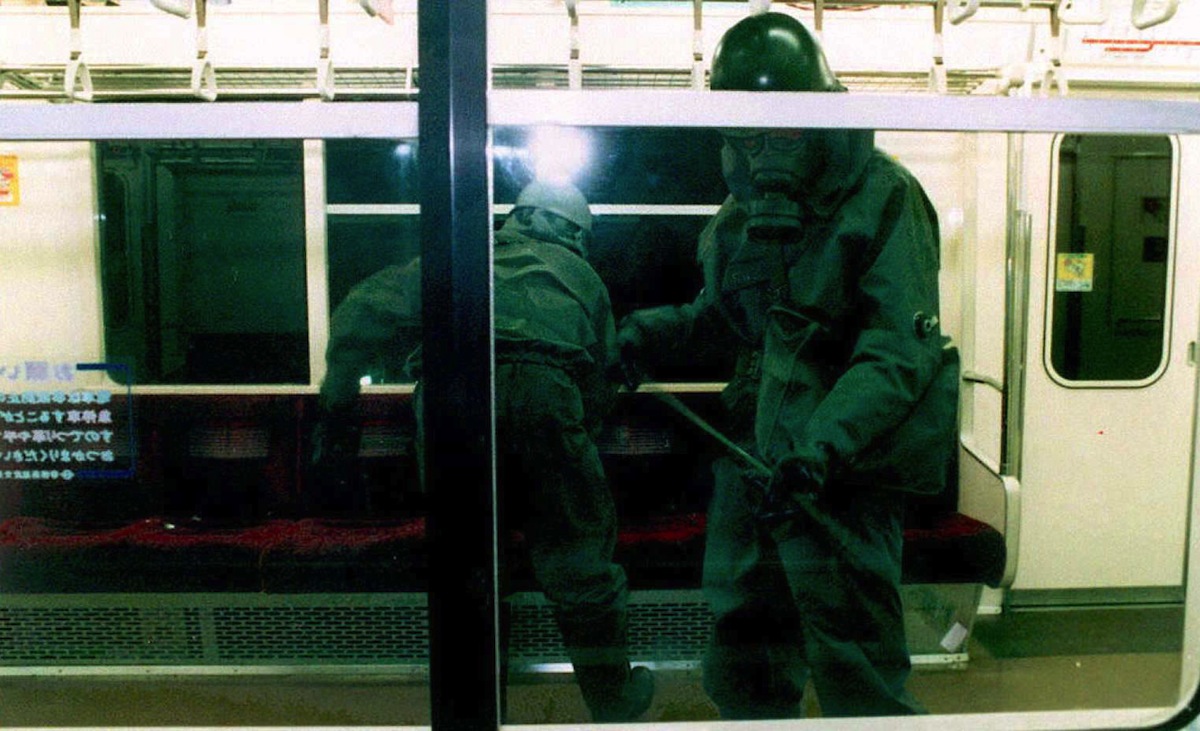

On this day, March 20, in 1995, 12 people were killed and thousands were sickened in Tokyo when members of Asahara’s cult, Aum Shinrikyo, released sarin during the Monday-morning rush hour in one of the world’s most crowded subway systems. Members of the cult used the tips of their umbrellas to puncture plastic bags filled with liquid sarin on five crowded cars before hurrying off at subway stops and leaving their fellow riders trapped with the toxic gas.

It was an unusual move for a religious movement based on Buddhist and Hindu principles and centered on the practice of yoga, but Asahara was an unusual spiritual leader. TIME described him, in a 1995 story about the gas attack, as a long-haired, bushy-bearded bully, “usually pictured wearing satiny pajamas,” who claimed he could levitate and promised to give his followers superhuman powers.

And although Aum Shinrikyo, which translates as Aum Supreme Truth, began as a yoga school in 1987, it evolved into a doomsday cult focused on the apocalypse that Asahara said was on its way. He prophesied that government efforts to shut down his sect would signal the beginning of the end, and that Armageddon would take the form of a chemical attack by the U.S., leaving only his own followers and 10% of the rest of the world. Asahara’s cult attracted a substantial following, despite his paranoia and violent tendencies. TIME explained:

By 1994 Aum boasted 36 Japanese branches with 10,000 members and a raft of international offices. Some, like the one in midtown Manhattan, offer little more than cheap videotapes of the master’s lectures to fewer than 100 members. But in Russia, another country experiencing a spiritual land rush, the cult has been successful: it has six offices and somewhere between 10,000 and 40,000 adherents.

The cult’s popularity took a hit after the subway attacks, especially when Asahara and 11 other members were convicted and sentenced to death. But diehard devotees stayed loyal, and the group, which has since changed its name to Aleph, even attracted some new members. TIME interviewed a disciple in 2002 who said that the spiritual leader’s inscrutability was part of his appeal.

“It was always hard to tell what he was thinking,” she told TIME. “He never did what you expected him to.”

Read TIME’s 1995 story about Shoko Asahara, here in the archives: JAPAN’S PROPHET OF POISON: Shoko Asahara

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com