Fantasy has escaped the fringe and come to the center of our lives and the stories we tell each other. It’s one wonderful tale. TIME’s Lev Grossman, author of The Magician’s Land, explains why fantasy is no longer just for nerds.

By Lev Grossman | August 19, 2014

Illustration by Nick Iluzada for TIME

![]()

hen I was a kid, in the 1980s, fantasy was not entirely OK. It had, let us say, some unpleasant associations. It was fringey and subcultural and uncool. In my suburban Massachusetts junior high, to be a fantasy fan was not to be a good, contented hobbit, working his sunny garden and smoking his fragrant pipeweed. It was to be Gollum, slimy and gross and hidden away, riddling in the dark.

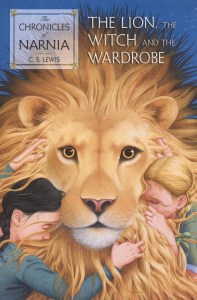

Not that this stopped me, or a lot of other people. C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, Piers Anthony, T.H. White, Fritz Leiber, Terry Brooks: I read them to pieces, and I chased them with a stiff shot of Dungeons & Dragons. But I did these things privately. In the wider world, of which I was reluctantly a part, a love of fantasy was a sign of weakness.

But that has changed. Something odd happened to popular culture somewhere around the turn of the millennium: Whereas the great franchises of the late twentieth century had tended to be science fiction—Star Wars, Star Trek, The Matrix—somewhere around 2000 a shifting of the tectonic plates occurred. The great eye of Sauron swiveled, and we began to pay attention to other things. What we paid attention to was magic.

I first realized this was happening in the late 1990’s, when Harry Potter started levitating up bestseller lists, but Harry was only the most visible example. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy came out in 1995 and was already a big deal. Robert Jordan was writing the Wheel of Time books. George R.R. Martin published A Game of Thrones in 1996. When I was a kid a big mainstream blockbuster movie based on a fantasy novel was a deeply implausible proposition, but The Lord of the Rings arrived in 2001 and won four Oscars. Eragon, World of Warcraft, Twilight, Outlander, Percy Jackson, True Blood, and the Game of Thrones TV show all came tumbling after.

And fantasy wasn’t just growing, it was evolving. People were doing weird, dark, complex, profane things with it. In 2001 Neil Gaiman published American Gods, an epic about seedy old-world deities trying to scratch out a living in secular strip-mall America. In Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell Susanna Clarke told the story of a rivalry between two wizards, in the Napoleonic Era, in gorgeous Austen-esque prose. That’s what did it for me personally: I got my hands on a copy of Jonathan Strange in May 2004, and by June I was writing a fantasy novel of my own. Clark’s book did everything literary fiction was supposed to do, and it did it with magic and fairies. That was a party I wanted to be at.

Fantasy wasn’t a fringe phenomenon anymore. It had become one of the great pillars of popular culture and, increasingly, the way we tell stories now. But why fantasy? And why now?

![]()

t’s interesting to compare the present moment to another one when fantasy was a big deal: the 1950’s, the decade when The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings were published, two of the founding classics of modern fantasy. By that time in their lives, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien had lived through some massive social and technological transformations. They had witnessed the birth of mechanized warfare – they were both survivors of World War I. They had seen the rise of psychoanalysis and mass media. They watched as horses were replaced by cars and gaslight by electric light. They were born under Queen Victoria, but the world they lived in as adults looked nothing like the one they’d grown up in. They were mourners of a lost world, alienated and disconnected from the present, and to express that mourning they created fantasy worlds, beautiful and green and magical and distant.

As it happens, we’ve lived through some changes too, albeit of a somewhat different kind. If my generation is remembered for anything, it will be as the last one that remembers the world before the Internet. You can’t compare what we’ve gone through to WWI, because that would be insane, but it’s not a trivial thing either. Lewis and Tolkien saw the physical world remade around them. The changes we’ve seen have been largely invisible but still radical: they happened in the sphere of information and communication and simulation and ubiquitous computation.

Which is why it makes sense that so much of the 20th century was preoccupied with science fiction, a genre that, among other things, grapples with the presence of technology in our lives, our minds, and our bodies, and with how our tools change the world and how they change us. Those issues are of paramount, urgent importance right now. But a countervailing movement is happening too: we’re also turning to fantasy. It’s counterintuitive, because fantasy is so often set in pre-industrial landscapes where technology is notable for its absence, but it must have something we need. We’re using it to ask questions. We like to celebrate this world, our new world, as a paradise of connectedness, a networked utopia, but is it possible that on some level we feel as disconnected from it as Lewis and Tolkien did from theirs?

Look at your phone, the avatar of the new networked reality. It’s not miles away from the kind of magic item you’d find in Dungeons and Dragons: it shows us distant things, lets us hear distant voices, gives us directions, divines the weather. We can speak to it and it obeys our commands, or more or less anyway. Our phones go everywhere with us, they present themselves as intimate friends—but they have a cold, alienating quality to them too. We don’t know how they work, or who made them, or where. We can’t open them and look inside. Our phones extract money from us, to make other people billionaires. They connect to us other people, but they create distance too. Our phones tempt us into ignoring our families and friends, even when they’re in the same room as us, in favor of a continuous IV drip of atomized bits of information and anonymous near-strangers in faraway cities. Maybe they’re not giving us the kind of connections we need.

God knows, characters in fantasy worlds aren’t always happy: if anything the ambient levels of misery in Westeros are probably significantly higher than those in the real world. But they’re not distracted. They’re not disconnected. The world they live in isn’t alien to them, it’s a reflection of the worlds inside them, and they feel like an intimate part of it. In the real world we’re busy staring at our phones as global warming gradually renders the world we’re ignoring uninhabitable. Fantasy holds out the possibility that there’s another way to live.

![]()

Lev Grossman is TIME’s book critic and its lead technology writer. He is also the author of the Magicians trilogy, including most recently, The Magician’s Land.