You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

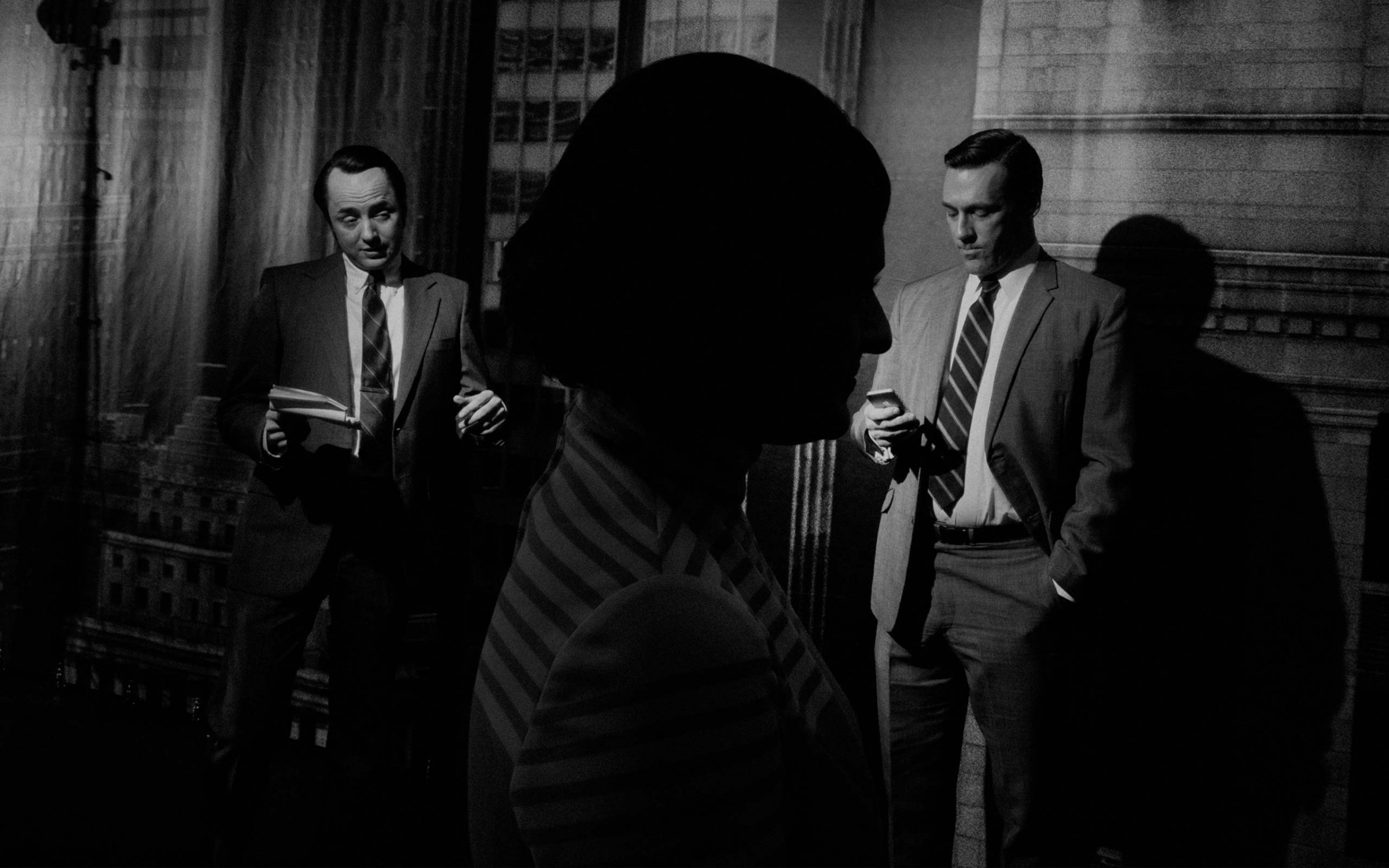

Don Draper is looking at his iPhone. O.K., not exactly: Star Jon Hamm is sitting in a Hallway, in his trademark slicked hair and wide-striped tie, checking texts. We’re between takes for the fifth episode of the seventh and final season of the iconic AMC series. It’s the modern equivalent of a 1960s cigarette break: women in done-up bouffants and men in chunky period glasses perch on modernist furniture and inhale data. If Sterling Cooper & Partners–the advertising agency where Mad Men is set–were actually in business, this would make one hell of an ad pitch to Apple.

Then the scene is reset, the iThingies stashed. The cameras roll. The actors fire up their herbal cigarettes. It’s 19somethingsomething again. (In order to visit the spoilerphobic set, I agreed not to reveal what exactly Don is up to or what year it is on the show, so let’s just call it 19somethingsomething.)

It’s jarring to see the 2010s intrude here after six seasons of watching AMC’s period drama re-create the years from 1960 to 1968 with OCD-like granularity. But in a way, the on-set mashup of rotary phone and smartphone doesn’t so much spoil the illusion of Mad Men as reveal what the show really is. Mad Men is a period piece, but one where the past haunts the present and the present haunts the past. It resonates with themes as old as the frontier and as current as today’s gender politics. Days after I visited the set, President Obama (reportedly a Peggy Olson fan) advocated equal pay for women in his State of the Union address by saying, “It is time to do away with workplace policies that belong in a Mad Men episode.”

On April 13, the conversation will swing back to Mad Men as it airs the first of its 14 remaining episodes (seven to air this year, seven next). “It’s starting to dawn on me, the finality of the experience,” the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, tells me later in his office, itself a mini-museum of tchotchkes, from 1960s campaign posters to old Philco TV ads. “I had an idea for a scene for Roger”–Roger Sterling, Don’s Scotch-marinated silver-fox colleague, played by John Slattery–“and as I was telling it to the writers’ assistant and she was writing it down, I was kind of overwhelmed. I realized I’d just thought of Roger’s last scene.”

Mad Men’s calendar is just about out of pages. It’s finishing up its time-lapse tour of a decade of American change through American culture. And it’s wrapping up its run as the signature show of a period in which the same kind of people who used to say “I don’t even own a television” were now arguing whether film and novels could even compete with TV drama. In more ways than one, the end of Mad Men will be the end of an era.

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW A SECRET?

Mad Men’s history stretches back to the last century–well, to 1999, when Weiner wrote the pilot while working on the Ted Danson sitcom Becker. The script follows adman Draper through his routine of drinking and pitching and shagging his beatnik girlfriend in Manhattan, ending with a return to–surprise!–his wife and kids in the suburbs. At the time, broadcast networks still made most TV dramas, and they weren’t in the market for a period piece about a heavy-drinking philanderer who sells cigarettes. The script languished, and Weiner got a job as a staff writer with The Sopranos.

HBO’s mob drama raised not only TV’s artistic aims but also the status of a channel once known largely for movie reruns. And when another such channel, AMC, wanted to make a similar move, it revived Weiner’s script. “We wanted to build premium television on basic cable,” says network president Charlie Collier. “We wanted to be a place where people would bring their passion projects.”

If The Sopranos aspired to the level of movies, Mad Men aspired to the level of literature. The first season–which premiered just a month after The Sopranos went off the air in 2007–played like newly unearthed Updike or Cheever stories, little tales of love and despair in the office towers and suburbs of 1960. It defied the usual structure of hour-long TV, making each episode unpredictable, a nighttime drive with the headlights on low. And it was built around a Jay Gatsby false-identity story: suave Don Draper, we learn, was born Dick Whitman, a prostitute’s orphaned son who grew up in Depression poverty and stole the identity of a Korean War comrade killed in action. American self-reinvention “is in our DNA,” Weiner says. “America is freshman year in college for every new immigrant. It’s [John D.] Rockefeller and Bill Clinton and Sam Walton, who came from rural poverty and invented themselves. And there’s a psychic cost to that.”

What Mad Men doesn’t have that The Sopranos did is, well, the Mafia: a big, popcorn-entertainment hook with life-or-death stakes. There are no whackings, though there have been a couple of lonely suicides. There are no guns–O.K., a few, but they’re not deployed the way TV usually uses them. Don’s frustrated wife Betty (January Jones) skeet-shoots her neighbor’s trained pigeons after an argument; ambitious junior executive Pete Campbell (Vincent Kartheiser) shows off a hunting rifle he bought for himself. It has yet to go off. (Take that, Chekhov.) “The show has never been a procedural in any way,” Hamm says. “It’s not like we have to get to the pot of gold or solve the mystery or kill the bad guy or anything like that.”

Instead, the show trusts in the power of style, subtlety and, above all, secrets, like the fact that Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) had a baby and gave it away just as her copywriting career was launching. The show is enchanted with the enigma of closed doors; several times, Don’s daughter Sally (Kiernan Shipka) opens a room to find adults in compromising positions, as in a disillusioning game of Let’s Make a Deal. There are few bombshells and cliffhangers, but in Weiner’s style of storytelling, a whisper can speak loudly.

And it works: the cultivated sense of mystery creates intense speculation. Fans scrutinize the show’s preseason poster art–commissioned this year from legendary graphic designer Milton Glaser–and its inscrutable “Next week on Mad Men” promos for clues like they’re the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album. When the show introduced enigmatic accounts man Bob Benson (James Wolk) in the sixth season, fan theories (he’s a spy! he’s a serial killer!) were far more exotic than the truth (he was a social climber who hid his background).

“I like the suspense of everyday life, honestly,” Weiner says. “There’s no one in the world today who sees an unidentified number on their cell phone and doesn’t have their heart racing.”

DETAILS, DETAILS

If Ebay married etsy, their starter home would look a lot like Mad Men’s studios. The costume department is crammed with aisles of madras plaid sport coats, jewel-tone office ensembles, pastel evening wear, all annotated by episode and season and labeled by character–Betty Draper’s peignoirs! Stan Rizzo’s tight pants!

If the stuff is not the star of Mad Men, it’s at least one of the show’s biggest selling points. Analysts have cited a “Mad Men effect” in everything from fashion–Banana Republic introduced a Mad Men line–to the vogue for whiskey-based cocktails. (In Season 2, Don crankily corrects Sally on how to properly muddle an old-fashioned, as a good father does.) The office Rolodexes are full of real vintage cards with retro KLondike-5-style phone numbers. The coffee tables are littered with day-and-date-appropriate issues of the New Yorker and LIFE. If there’s a pile of papers on a desk, someone from the crew typed them–that’s typed on a typewriter, not printed on a computer. Mad Men’s fans have embraced its fussy authenticity, going into a tizzy last season after Joan Harris (Christina Hendricks) fleetingly mentioned Le Cirque, a Manhattan restaurant that did not open until 1974.

But the show’s eye candy is also brain candy; each object, reference and decor decision is grounded in a specific philosophy of story, character and history. For instance, shows about the 1960s often look too much like “the 1960s”: the too-perfect clichés of Eames and Twiggy and Haight-Ashbury. When researching wardrobe for a given year, says costume designer Janie Bryant, she consults the Sears and JCPenney catalogs, because “a lot of those everyday references are more important than what Paco Rabanne and Pierre Cardin were doing.” Mad Men’s 1960s houses have furnishings from the 1950s and before, because the past has its own past.

The designers make all these calls with extensive input from Weiner. When Mad Men introduced a minor character in Season 4–Ida Blankenship, an elderly secretary assigned to Don after he’d slept with a younger one–Weiner “gave us a whole list of things he wanted on her desk,” says set decorator Claudette Didul. “Snow globes. A little Eiffel Tower, as if she’d traveled. Some seashells.” (Over the season, we learn that she’d gotten around, geographically and sexually, when she was younger.) When Don and his partners launched a new ad agency, says production designer Dan Bishop, Weiner wanted the new offices to have a more open, “rabbit warren” look, to get across a historical idea that “the control and precision of the 1950s is breaking down.”

Other times the cues are vaguer, as with the introduction of Roger’s blindingly white, futuristic new office the same season. “In the first script, [copywriter] Freddy Rumsen comes in and says, ‘It looks like an Italian hospital in here,'” says Didul. “So we had to figure out, What does an Italian hospital look like?”

MAKING HISTORY

All that design fussiness ties in to Mad Men’s larger mission: to embody history without being a cliché of history–a big challenge when you’re dealing with a decade more picked over than a West Hollywood vintage shop. We’re used to seeing the 1960s as the story of the baby boom changing the world. Mad Men gave us characters just outside that change. Executives, accountants, housewives–squares.

“The average person didn’t go to Woodstock,” says Weiner. “They saw the documentary a year later.” Don and his partners chase youth for a living (and often sleep with it), but they’re frightened of its anarchy. In an early episode, Don warns his staff against using space-age imagery in a deodorant ad. “Some people think of the future and it upsets them,” he says. “They see a rocket and they start building a bomb shelter.” Mad Men’s is a history told by the losers, albeit losers with money; the one time Don’s agency takes a political client, it is Richard Nixon–in 1960.

The thing about Mad Men’s portrait of the 1960s is that it’s also a portrait of the 1930s–when orphan Dick Whitman grew up in a whorehouse in Pennsylvania–and the 1950s and even today. Its history is written in pencil, erased and rewritten, so you can always read the traces of what’s underneath. The early episodes had some fun with it-was-a-different-time-then imagery (Sally plays astronaut with a dry-cleaning bag over her head), but Mad Men is more interested in commonalities. Weiner says the standard hack line that America lost its innocence in the ’60s is condescending–because we didn’t have it to lose. “The heart of the show is, Look at the people who are older than you and stop assuming that they’re a bunch of codgers who’ve never lived a life,” he says. “They weren’t like Ozzie and Harriet. They were laughing at Ozzie and Harriet the same way we do.”

The toughest parts of history to write, Weiner admits, are the most obvious: the JFK assassination, the counterculture. (“When you have your first hippie, you’re like, ‘Am I just doing Dragnet here?'”) Mad Men approaches history best at an oblique angle. It implies the bloodbath of Vietnam at an office party when a drunk staffer on a riding lawn mower runs over a new executive’s foot. (“Just when he got it in the door,” Roger quips.) The Cold War becomes a metaphor when Pete runs into his father-in-law at a midtown brothel and assumes (wrongly) that the older man will never tell because it’s “mutually assured destruction.” This, Weiner argues, is how people really experience history. “Not everybody’s going around talking about the war,” he says. “There’s a war going on now and you don’t hear about it unless you read the New York Times.”

You’d expect Weiner to be steeped in the minutiae of history. What’s surprising is how much he says his writing is shaped by today’s events. In the 1964 of Season 4–which aired just after the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010–a market researcher complains, “If they pass Medicare, they won’t stop until they ban personal property.” Season 6, set in 1968, was the most explicitly focused on big historical events. But instead of taking the usual angle–everything’s changing–Weiner was interested in what didn’t change: revolutions were quashed, the Soviets rolled into Prague, MLK and RFK were killed, and in the end, Nixon, the candidate from 1960, was elected President. It was all inspired, he says, by the anxieties and disappointments of our time, when change didn’t exactly arrive as advertised, in Washington, on Wall Street or in Egypt.

The show echoed that theme in Don, who tries to change his ways only to end up cheating on his new wife Megan (Jessica Paré). Mad Men is often a story of men who repeat the same mistakes. But title notwithstanding, it’s equally the story of its complex women: Betty, who bought into a housewife role that doesn’t fit her and is losing its currency; Sally, who sees her mother as an enemy and her father as a stranger; Joan, proudly feminine and iron-willed. (The show hasn’t depicted African Americans nearly as much, a lacuna Weiner defends because it would be “a lie” to portray SC&P’s world as integrated.) Unusually for a TV drama, Mad Men has a majority of female writers, though Weiner has the bulk of the writing credits.

It’s in Peggy’s story that Mad Men’s feminism seems most like today’s, because she’s most like us. She’s leaning in not from ideology but instinct; she’s not a crusader so much as a working stiff who wants a good job and a fair shake and to get laid now and then. “She didn’t know the phrase the glass ceiling,” Moss says. “Day to day, it’s just about trying to get your idea heard and maybe someone’s being an a–hole to you and you didn’t get enough sleep.” In Season 4’s “The Beautiful Girls,” Peggy argues with her leftist-reporter boyfriend about whether black people or women have it harder in America. “Most of the things that Negroes can’t do, I can’t do either, and nobody seems to care,” she says. He teases her: “All right, Peggy, we’ll have a civil rights march for women.” Change a few details and they could be arguing the Barack Obama–vs.–Hillary Clinton primary.

Peggy and Don are opposites, and they’re soul mates; you can’t really understand one without the other. The show’s opening credits show us the Saul Bass–like silhouette of a man who looks a lot like Don falling from an office tower. But if his descent is half the story of Mad Men, Peggy’s ascent is the other half. Her elevator is going up, his is going down, yet they’re more alike than anyone on the show, creatively driven, stubborn, secretive. They’re the Janus face of Mad Men, he looking toward his past, she toward our future.

THE BEST, AND WORST, OF TIMES

In last season’s finale, Don faces his past more directly than ever. After a successful pitch to Hershey, for which he invents a story about being bought a chocolate bar by his loving dad, something snaps and he has to tell the truth: one of the prostitutes he grew up with gave him a Hershey for going through her johns’ pockets. It’s moving, heartbreaking–and mortifying. For the first time, one of Don’s improvised, lyrical pitches backfires. SC&P puts Don on leave and, realizing he has raised his kids as strangers to him, he drives them out to see the house where he grew up. Like the maturing America, Don has run out of frontier. He can’t just light out for the territory like Huck Finn anymore. He has to stay where he is and fix himself, or fail.

Is Don’s decision liberating or confining? That’s a theme of the Season 7 premiere, which finds some characters feeling freed by the changes in their lives, others unmoored. There’s a free-floating sense of primal menace. In Season 6, we could hear police sirens from Megan and Don’s balcony; now, outside a house in the Los Angeles hills, we hear the howls of coyotes. You can feel entropy even in the show’s art and design. Mad Men began in the gray aftermath of the 1950s, then it blossomed into bold primary color, and now it feels like the fruit is getting overripe. His career and marriage shaken, Don is feeling his way back slowly, like a drunk looking for his keys. “I keep wondering,” he says, “have I broken the vessel?”

After his scene finishes shooting, I ask Hamm if he thinks Don is fixable, or if we should even want him fixed. “I would hope that we see the guy find balance, that we see him find peace,” Hamm says. But, he adds, “I’m always surprised when people are like, ‘I want to be just like Don Draper.’ You want to be a miserable drunk? You want to be like the guy on the poster, maybe, but not the actual guy. The outside looks great, the inside is rotten. That’s advertising. Put some Vaseline on that food, make it shine and look good. Can’t eat it, but it looks good.”

We’ll have to wait to see if Don’s redemption is more than Vaseline-deep. Inspired by the spectacular success of the two-part final season of Breaking Bad, AMC asked Weiner to deliver Mad Men’s ending in two chunks, seven episodes each for 2014 and 2015. Weiner and crew are now at work on the second half, which means the finale will be done–and will have to be kept secret–for nearly a year before it airs. (Moss jokes that to prevent spoilers, Weiner should quarantine the cast in a hotel, “like on The Amazing Race.”)

However Mad Men ends, it will leave behind a TV-drama business much bigger in material and ambition. TV’s top dramas–and drama-tinged comedies like Girls and Louie–have a hold on the culture that only a handful of books or movies do anymore. House of Cards and Homeland transfix politicos, while HBO’s literary murder mystery True Detective absorbed viewers in the fiction of Lovecraft and the philosophy of Nietzsche. Last year, director Steven Soderbergh said he was quitting the movies, frustrated by Hollywood’s lack of interest in creative visions that don’t involve blowing stuff up. His next project, a 10-part series called The Knick, premieres on Cinemax this summer. This winter, the New York Times Book Review asked, “Are the New ‘Golden Age’ TV Shows the New Novels?” comparing Mad Men and company to the serial novels of Charles Dickens.

Dickens may sound like a strange role model for midcentury-modernist Weiner. But as he’s been finishing the story, he’s been thinking about A Tale of Two Cities (which gave its title to a Season 6 episode). People remember how Dickens in 1859 describes the French Revolution: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” But they don’t always remember what follows: “In short, the period was so like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.” In other words, the world back then was amazing and it was going to hell–just like today, just like always, even if we like to believe our own era is uniquely troubled.

That’s very much the spirit of Mad Men. But, Weiner says, there’s also a hopeful flip side to Dickens’ story, which ends with a flash-forward to Paris decades after the guillotines. “All this will pass,” Weiner says. “This is a time when the streets are running with blood, and then there will be a time when flowers are growing and everyone will forget it, but it will still be the same place.”

So too with Mad Men’s America. Weiner’s drama is not the kind that’s likely to end with blades falling and heads rolling. But to paraphrase A Tale of Two Cities’ Sydney Carton, it will have taught TV to do far, far better things than it has ever done.

GET EVEN MADDER WITH EXCLUSIVE PHOTOS AND VIDEO AT time.com/madmen

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com