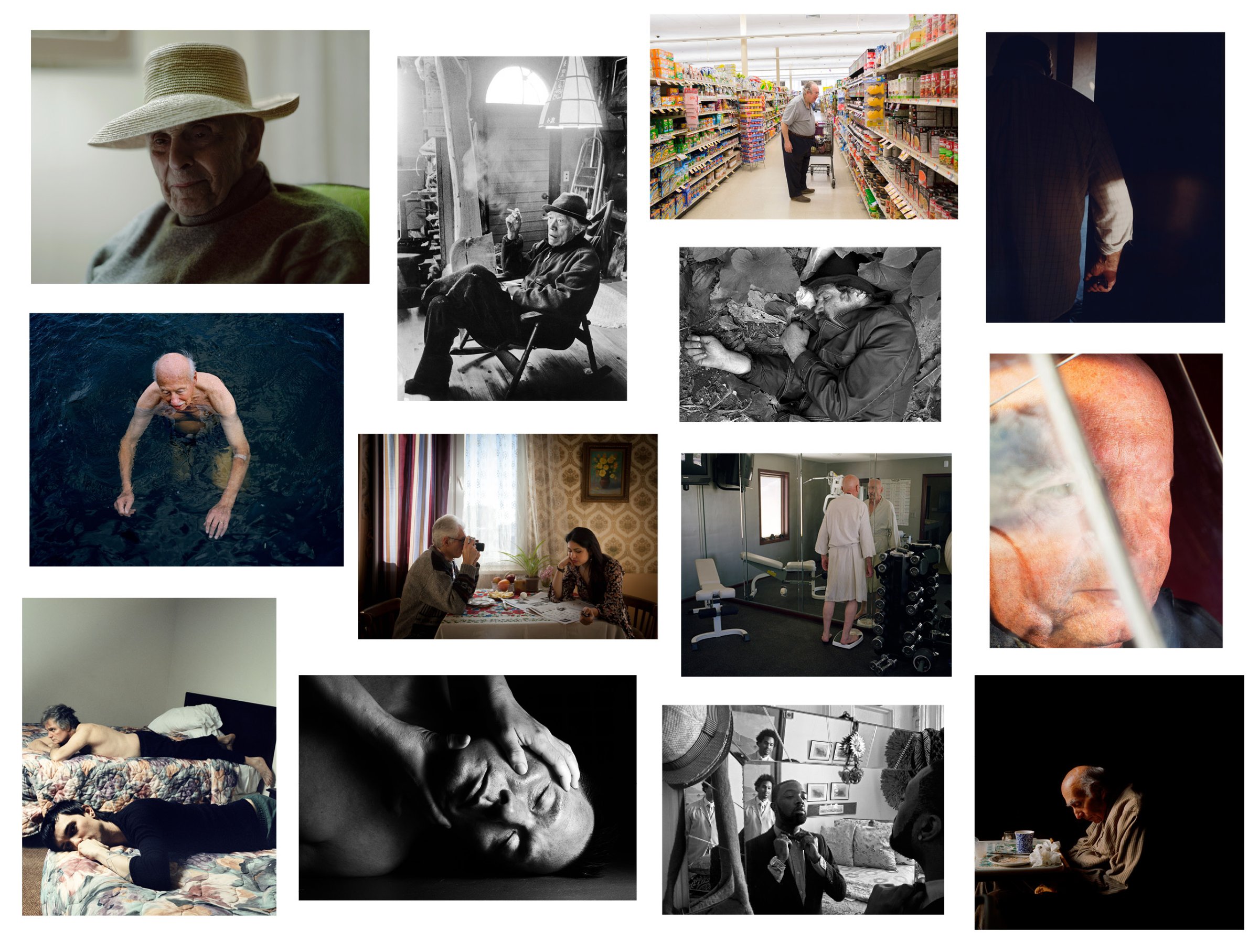

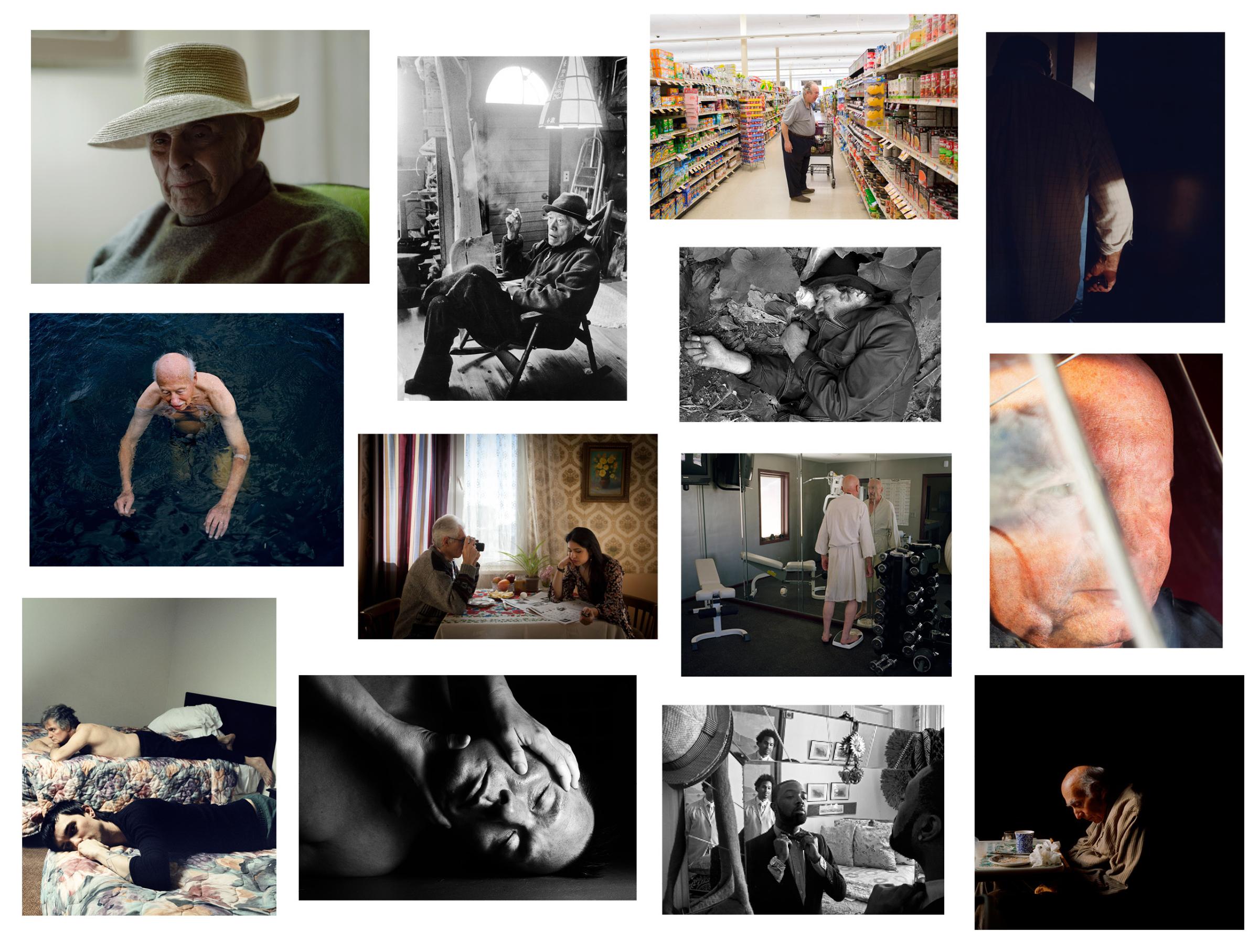

TIME asked 14 photographers who’ve dedicated themselves to making extensive work about their families to reflect on their experiences photographing their fathers—and to describe which of their own photographs moved them most.

This selection of 14 photographers deconstructs traditional portrayals of fatherhood with a variety of approaches to reveal the complexity of modern fathership. Some image makers, like Mitch Epstein, attempt to challenge the traditional patriarchy of the father as the breadwinner to reveal the actual men in the role as much more fragile, sensitive and complex than often is depicted in media and art history. In his book Family Business, a son portrays his father at the end of his career while looking at the American economy shifting its focus from family-owned businesses to corporate big box stores.

Other photographers call into question how our relationships with our fathers change when an illness alters the parental dynamic. Their photographs attempt to document the frailty of these men with extreme care and sensitivity. Speaking about her work Amanda Tetrault says that “it is the hardest photograph I have ever taken of Phil.” Her father Phil Tetrault suffered from schizophrenia and has lived on and off the streets of Montreal for the past 30 years. “It embodies everything that is conflicted about Father’s Day for me. The pain of knowing that someone you love needs help and is in crisis, and anger at never having known what being fathered might feel like.”

Some photographers use their fathers as model and muse for their art practice, which often tends to coincides with changes in their relationships. Artist Michael Marcelle’s father has become a recurring character in his work and makes his practice a family affair. “We both took turns feeling uneasy about the work, but ultimately kept returning to it, because it was ours, because it was a way to talk about death and destruction and family without words,” Marcelle says. “It was something I never could have done without him.”

Zun Lee employs the camera to question the biological necessity of fatherhood all together. After discovering his own African American heritage he began documenting the roles of “father figures” in African American families for several years to examine misperceptions of black fatherhood. “This work hits close to home for me,” he says. “I’m paying homage to the many African American men that nurtured and loved me despite my biological father not being present in my life. Men that embodied parenthood in ways that didn’t (and didn’t need to) correspond to traditional notions of the nuclear family.”

Dad, Hampton Ponds III, 2002 From the book Family Business by Mitch Epstein

“This is my father. Bill Epstein was a furniture merchant and landlord in the small New England town of Holyoke, Massachusetts. Through my dad and Holyoke, I confronted the faltering American dream: enterprising individuals were losing out to a supersize-me ideal: bigger was better. Big malls, big box stores, big drinks. Small town America had succumbed to a corporate takeover.

“Meanwhile, my father treated his customers like family; when something he had sold broke, he went to their homes and fixed it. He couldn’t compete with the chain stores that sold huge quantities of stuff made in China on the cheap. No one fixed those wares. When they broke the customer just threw them out and bought another.

“In the year 2000, my father was in crisis. One of the buildings he owned had burned to the ground and taken an entire city block with it; and his furniture store was on the verge of bankruptcy. I went home to help and there was nothing I could do. But there was a story to tell. So I spent the next three years making pictures and films to tell his story, which also became the story of a dying town. I called the project Family Business.”

From the series Mornings (with you) by Diàna Markosian

“This is an image of my father and I together at breakfast. I was 7 when I was separated from him. My mother woke me up in our home in Russia and told me to pack my belongings. She said we were going on a trip. The next day we arrived in America. We never said goodbye to him. When I would ask my mother about him, she would tell me to forget him. I eventually did.

“It wasn’t until I was an adult that I traveled back to Armenia to find him. My father didn’t recognize me. I didn’t recognize him either… I felt out of place. Photography has in a way allowed me to confront this part of my life. My father and I began to take images of each other, the space between us as a way of working through the void in our relationship. This image was taken at his home, 20 years after we were separated.”

From the book Phil and Me by Amanda Tetrault

“This is my father Phil Tetrault, passed out drunk in an empty lot in downtown Montreal. It is the hardest photograph I have ever taken of Phil, who suffers from schizophrenia and has lived on and off the streets of Montreal for the past 30 years. It embodies everything that is conflicted about Father’s Day for me. The pain of knowing that someone you love needs help and is in crisis, and anger at never having known what being fathered might feel like.

“I forced myself to take this picture, and am pleased I did because it has helped me work through the tough feelings, and has allowed me to raise awareness about the impact of mental illness on an individual, and the struggle their families can face.

“I share this image now on Father’s Day, to thank Phil for the things I have learnt from our relationship and his illness, and to acknowledge how hard father’s day is for those of us who have experienced trauma because of this relationship.”

From the series Not Without My Father by Ryan Pfluger

“The purpose of starting Not Without My Father was an attempt to create some sort of relationship with my father, using photography as therapy. At the start we were barely even able to have conversation with each other. I had no idea whether it was purely going to be constructed or lead to a lasting relationship between us.

“This photograph, while staged like the rest, is the most honest. At one of the many run down motel rooms we stayed at during a short road-trip, I kept my extended release by my bedside and every so often when it felt right over the course of the evening I would take a frame.

“While completely cathartic, it also is a representation of the exhaustion from truly addressing and mending a broken relationship.”

“Dad in Mirror” from the series Sunday El Rancho by Damien Maloney

“I was in the weight room at my Dad’s house in Phoenix when he walked in nude, and noticing me, turned around and returned wearing a robe to weigh himself on the scale before his shower. There are televisions in every room of his house.

“After I took this photo my father noted that he weighs himself without clothes so the weight of them isn’t a factor. I argued that his robe could only weigh ounces and that also he is using a spring scale, which isn’t very accurate. We often get into tiny arguments like this where he is focused on the details and I encourage him to consider the larger context. He has since bought a new scale.”

“I started photographing my dad as a way to make sense of the time we spent together. We planned this two-week trip through northern Arizona a few years back and I was anxious about it so I decided I would try to take some pictures of him.”

At home with James Reynolds and Jerome Williams. Harlem, NY. Sept. 2011. From the series Father Figure by Zun Lee

“This is one of the earliest images from my Father Figure project but still my favorite. I worked with African American fathers and families for several years to examine why black father absence stereotypes persist, despite ample research evidence showing that black fathers are no worse than fathers of other ethnicities.

“This work hits close to home for me. I’m paying homage to the many African American men that nurtured and loved me despite my biological father not being present in my life. Men that embodied parenthood in ways that didn’t (and didn’t need to) correspond to traditional notions of the nuclear family. It is my recollection of their care that served as inspiration for this work and allowed to come to terms with my own past.

“This image shows Jerome Williams at his father’s apartment, attempting to tie a bow tie for the first time in his life. Moments ago, his dad James Reynolds showed Jerome how to do it. James is now watching his son carefully from a distance, visibly pleased to see Jerome being successful on his first attempt. There are so many layers of meaning here: James isn’t Jerome’s biological father but their family bond is obvious. The scene epitomizes paternal guidance but also represents a rite of passage into adulthood for Jerome. For me, there is a bittersweet personal context: I still don’t know how to tie a bow tie, my own father hadn’t been there to teach me. The moment reminded me of what I had and didn’t have growing up.”

From the book Days with My Father by Phil Toledano

“My father, wearing my mother’s sun hat. I’m not even sure if he knew it was hers. Or maybe he did, and that was the point. I’ve passed on things he used to say to me, to my six year old daughter, so now he’s met her, sort of.”

Dad at the Super Stop & Shop in Brooklyn, New York, April 2016, by Lauren Fleishman

“This is a portrait of my dad in the soup aisle of a Stop & Shop supermarket. Having lived abroad for years, I could recognize how special it was to just be there and spend time with my father. My dad is a character. Being together at the supermarket was a big part of my childhood and everything familiar that I miss.”

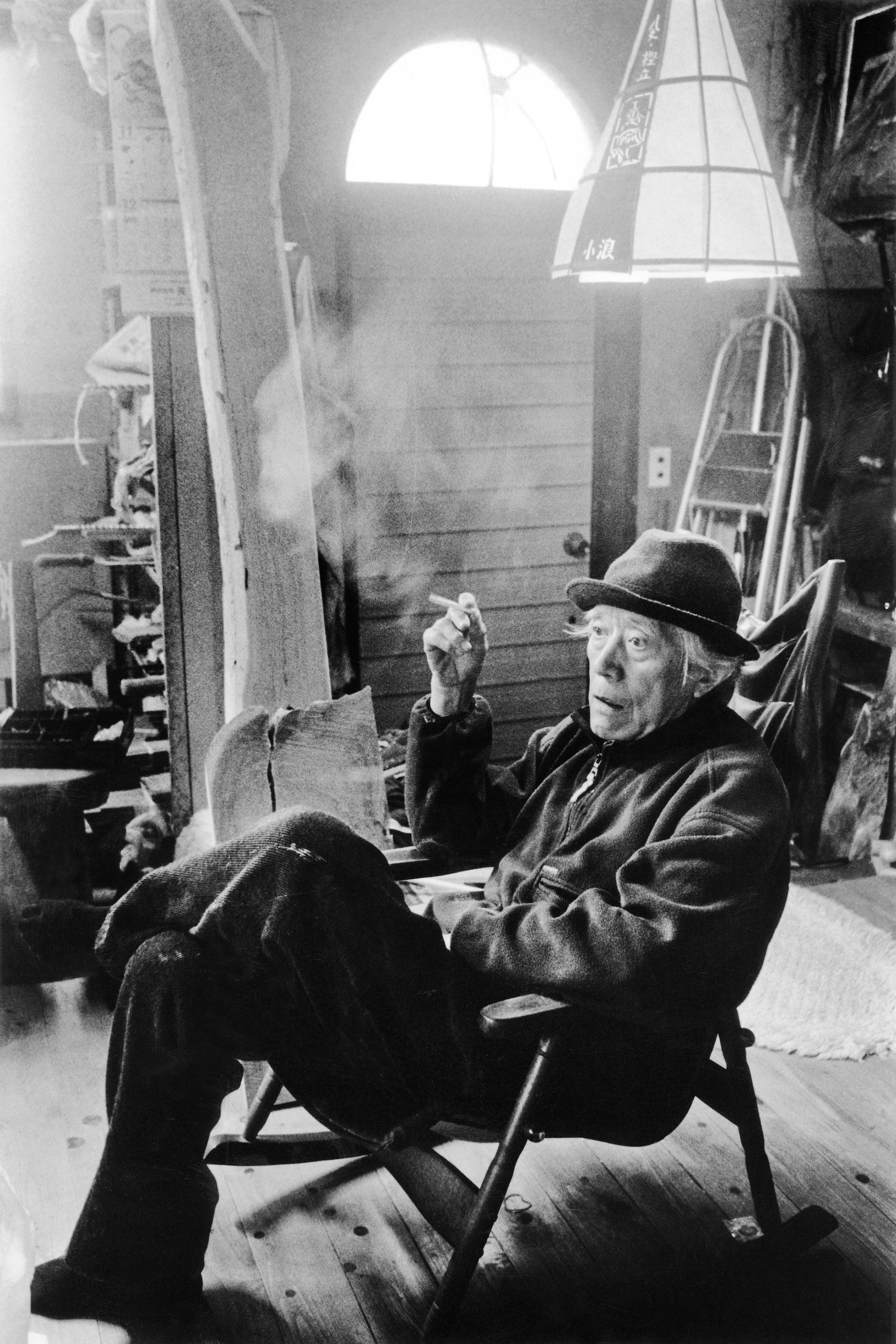

From the book Looking at My Father, by Jiro Konami

“This is the first photo that I made of my father. I felt shy, so I took the photo without saying anything, covered my face with the camera. Since then, I had been shooting his photos for eight years. The first time only comes once.”

From the series Kokomo by Michael Marcelle

“I started photographing my father out of necessity.

“I was in a post-collegiate haze looking for something, anything to photograph, and found myself driving to my hometown on my days off, asking him to come with me to the beach to take pictures.

“After a hurricane swept most of our town away, I began to abstract my father and the world around him into something alien and hallucinatory, something I might have seen in a horror film or a dream. I had no idea what I was doing, but knew I wanted to do be doing it with him, about him. We created something strange, something that was at once separate from ourselves and yet inexorably part of us, something that for all of my attempts to obscure a biographical narrative, felt starkly intimate and deeply personal. We both took turns feeling uneasy about the work, but ultimately kept returning to it, because it was ours, because it was a way to talk about death and destruction and family without words. It was something I never could have done without him.

“Recently I’ve begun new projects and have stepped away from this series, but every now and then I’ll drive out to the ocean and make something with my father, my muse. I do it out of necessity.”

Dad, Overland Park, Kansas, 2005, from the book Stuff I Gotta Remember Not to Forget by Darin Mickey

“Over a decade has passed since I took this photograph of my father sitting in the backyard after mowing the lawn on a humid August evening. For many years I saw exhaustion when I looked at this image. A picture of a man exhausted from a life of cold-calls and the endless hustle of being a salesman, a father, and a husband.

“In more recent years when I look at this photograph I see patience. The patience to accept a life of work with few rewards in order to provide for a family. The patience to sit still after doing battle with the push mower so your son can take another awkward photograph.

“As I continue to approach the age my father was in this picture I’m pretty sure what I see in it will differ from what I see in it today. The only thing I can say with some degree of certainty is that no matter what happens to me, my father, or this photograph someone will still have to continue to cut that always-growing, indifferent patch of grass.”

From the book Two People by Sean Lee

“I have been photographing my parents for a number of years now and I plan to continue doing so for as long as they are alive. My parents and sisters are the only people whom I share a relationship with, without my own choosing. To have them in my life is a gift. We live in the same three-room apartment and making pictures is a part of our life at home.

“This picture is a precious image to me. It reminds me of the religious iconography of saints. Held in my mother’s hands, my father looks to me like a fallen martyr. In a way, this is very true of his life and what he means to me and our family.

“My father grew up poor and tough. Like many other people from his background and generation, he was involved with the triads at a young age and had a reputation as an intimidating figure.

“Over the years, he has mellowed down. Traditional cultures tend to produce men who are stoic and unaffectionate. As such, we had a complicated relationship when I was younger. As I got older, I began to develop a deep appreciation for the sacrifices he had to make over the decades as the sole breadwinner of the family and simply, for the person he is.”

From the series Still Here by Lydia Goldblatt

“When my dad was getting older and more frail, I had the privilege of being close by, of being able to spend time with my parents during the days and evenings. I witnessed the small, repeated rituals of the day, and the slow passing of the hours. I made photographs over a span of about three years in which I could explore many of these subtle shifts: the love and loss that were part of the house and our relationships, the knowledge of mortality and time passing that infused the moments, the light, the shadows and us.

“This particular photograph was made after a meal. Some of the things that move me about it are not visible in the image. I know that the light coming into the room is from the garden that he loved, and that he loved looking out onto when he no longer walked within it. I know that, although the room is darkened, my mother and I were both there with him, my mother sitting on the bed behind, and me with my camera. Although the photograph depicts a person alone, he is not. My father feels at rest here, and the poignancy of the darkness is offset by the peace and security of the midday ritual of toast and tea. For me, this photograph is also one of connection: of the relationships that existed between us, of my father’s place in this room and this home, and the privileged connection I had with him through the ability to make photographs as well as being his daughter.”

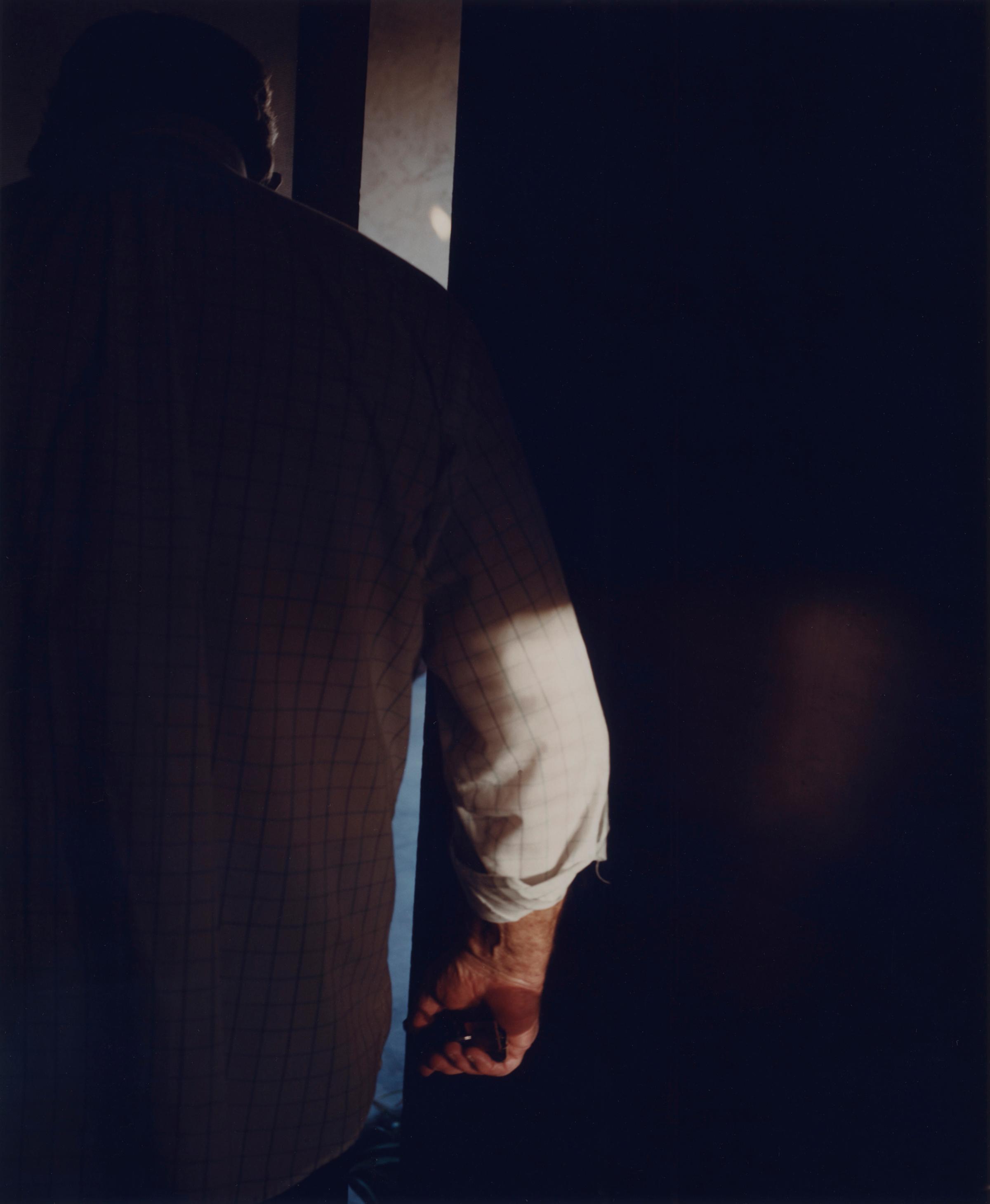

From the book Family Tree by Glen Earler

“As a father, and after losing mine, I came to realize how fragile life really is. I also understand the love a father has for their children and how difficult that is to relay to them, no matter how many times one might try. As a son, I miss my father dearly and wish that he was still here with us watching my daughters grow up and experiencing that for both himself and for them.

“I chose this photograph because it was the last time I saw him and also it was the last time my daughters saw him and he them. This image wonders through my memory on a daily basis, also in motion, him walking through the frame and out the door. I followed him to his truck where we spoke for a few minutes, I hugged him and then he drove off.

“The stillness of this frame was lucky in many ways but yet must have been a Godsend at the same time. There is only one frame, with no variation but it speaks about my father, physically and emotionally along with the strength he carried with him that helped him through his life and the stories he mostly kept hidden away. It reminds me of his presence and how he would complain about his hands and how swollen they often were. I’m fortunate I have these images of him but even more so, the memories that accompany them.”

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @paulmoakley.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com