One afternoon in late February, Gennady Kernes, the mayor of Kharkov, Ukraine’s second largest city, pushed his wheelchair away from the podium at city hall and, with a wince of discomfort, allowed his bodyguards to help him off the stage. The day’s session of the city council had lasted several hours, and the mayor’s pain medication had begun to wear off. It was clear from the grimace on his face how much he still hurt from the sniper’s bullet that nearly killed him last spring. But he collected himself, adjusted his tie and rolled down the aisle to the back of the hall, where the press was waiting to grill him.

“Gennady Adolfovich,” one of the local journalists began, politely addressing the mayor by his name and patronymic. “Do you consider Russia to be an aggressor?” He had seen this loaded question coming. The previous month, Ukraine’s parliament had unanimously voted to declare Russia an “aggressor state,” moving the two nations closer to a formal state of war after nearly a year of armed conflict. Kernes, long known as a shrewd political survivor, was among the only prominent officials in Ukraine to oppose this decision, even though he knew he could be branded a traitor for it. “Personally, I do not consider Russia to be an aggressor,” he said, looking down at his lap.

It was a sign of his allegiance in the new phase of Ukraine’s war. Since February, when a fragile ceasefire began to take hold, the question of the country’s survival has turned to a debate over its reconstitution. Under the conditions of the truce, Russia has demanded that Ukraine embrace “federalization,” a sweeping set of constitutional reforms that would take power away from the capital and redistribute it to the regions. Ukraine now has to decide how to meet this demand without letting its eastern provinces fall deeper into Russia’s grasp.

The state council charged with making this decision convened for the first time on April 6, and President Petro Poroshenko gave it strict instructions. Some autonomy would have to be granted to the regions, he said, but Russia’s idea of federalization was a red line he wouldn’t cross. “It is like an infection, a biological weapon, which is being imposed on Ukraine from abroad,” the President said. “Its bacteria are trying to infect Ukraine and destroy our unity.”

Kernes sees it differently. His city of 1.4 million people is a sprawling industrial powerhouse, a traditional center of trade and culture whose suburbs touch the Russian border. Its economy cannot survive, he says, unless trade and cooperation with the “aggressor state” continue, regardless how much Russia has done in the past year to sow conflict in Ukraine.

“That’s how the Soviet Union built things,” Kernes explains in his office at the mayoralty, which is decorated with an odd collection of gifts and trinkets, such as a stuffed lion, a robotic-looking sculpture of a scorpion, and a statuette of Kernes in the guise of Vladimir Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union. “That’s how our factories were set up back in the day,” he continues. “It’s a fact of life. And what will we do if Russia, our main customer, stops buying?” To answer his own question, he uses an old provincialism: “It’ll be cat soup for all of us then,” he said.

Already Ukraine is approaching that point. With most of its scarce resources focused on fighting Russia’s proxies in the east, Ukraine’s leaders have watched their economy fall off a cliff, surviving only by the grace of massive loans from Western institutions like the International Monetary Fund, which approved another $17.5 billion last month to be disbursed over the next four years. But that assistance has not stopped the national currency of Ukraine from losing two-thirds of its value since last winter. In the last three months of 2014, the size of the economy contracted almost 15%, inflation shot up to 40%, and unemployment approached double digits.

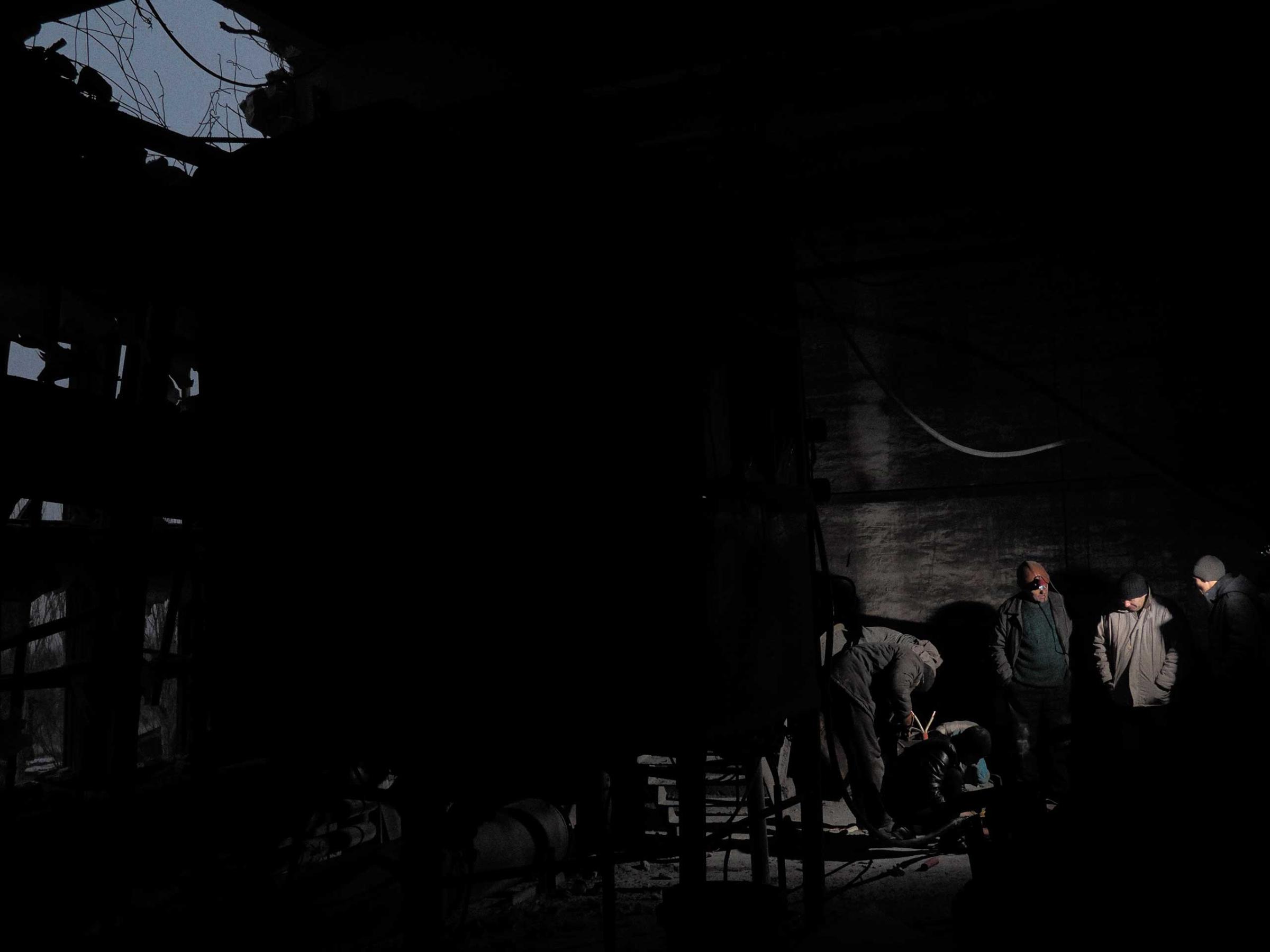

Beneath the Front Lines of the War in Eastern Ukraine

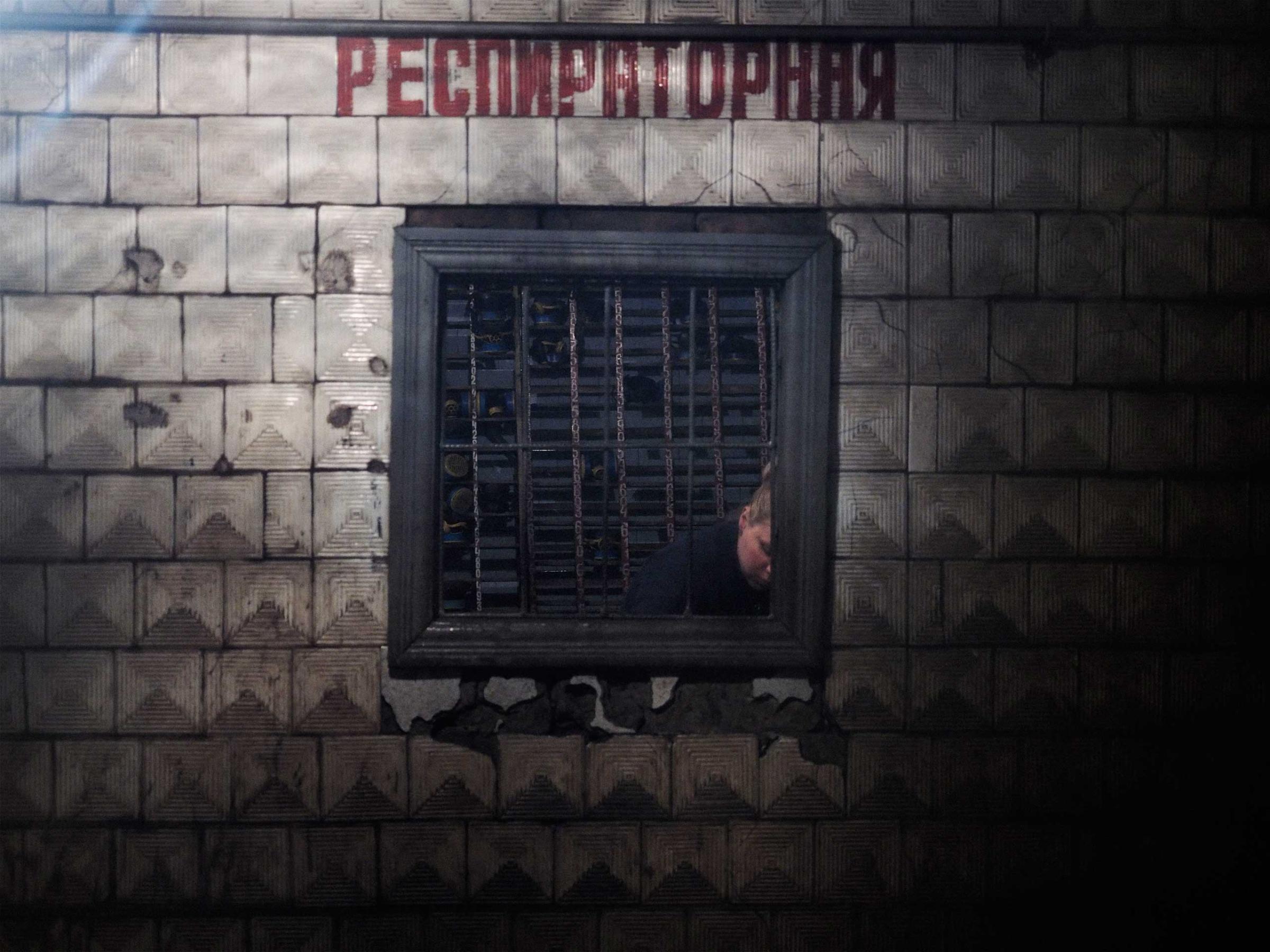

But that pain will be just the beginning, says Kernes, unless Ukraine allows its eastern regions to develop economic ties with Russia. As proof he points to the fate of Turboatom, his city’s biggest factory, which produces turbines for both Russian and Ukrainian power stations. Its campus takes up more than five square kilometers near the center of Kharkov, like a city within a city, complete with dormitories and bathhouses for its 6,000 employees. On a recent evening, its deputy director, Alexei Cherkassky, was looking over the factory’s sales list as though it were a dire medical prognosis. About 40% of its orders normally come from Russia, which relies on Turboatom for most of the turbines that run its nuclear power stations.

“Unfortunately, all of our major industries are intertwined with Russia in this way,” Cherkassky says. “So we shouldn’t fool ourselves in thinking we can be independent from Russia. We are totally interdependent.” Over the past year, Russia has started cutting back on orders from Turboatom as part of its broader effort to starve Ukraine’s economy, and the factory has been forced as a result to cut shifts, scrap overtime and push hundreds of workers into retirement.

At least in the foreseeable future, it does not have the option of shifting sales to Europe. “Turbines aren’t iPhones,” says Cherkassky. “You don’t switch them out every few months.” And the ones produced at Turboatom, like nearly all of Ukraine’s heavy industry, still use Soviet means of production that don’t meet the needs of most Western countries. So for all the aid coming from the state-backed institutions in the U.S. and Europe, Cherkassky says, “those markets haven’t exactly met us with open arms.”

Russia knows this. For decades it has used the Soviet legacy of interdependence as leverage in eastern Ukraine. The idea of its “federalization” derives in part from this reality. For two decades, one of the leading proponents of this vision has been the Russian politician Konstantin Zatulin, who heads the Kremlin-connected institute in charge of integrating the former Soviet space. Since at least 2004, he has been trying to turn southeastern Ukraine into a zone of Russian influence – an effort that got him banned from entering the country between 2006 and 2010.

His political plan for controlling Ukraine was put on hold last year, as Russia began using military means to achieve the same ends. But the current ceasefire has brought his vision back to the fore. “If Ukraine accepts federalization, we would have no need to tear Ukraine apart,” Zatulin says in his office in Moscow, which is cluttered with antique weapons and other military bric-a-brac. Russia could simply build ties with the regions of eastern Ukraine that “share the Russian point of view on all the big issues,” he says. “Russia would have its own soloists in the great Ukrainian choir, and they would sing for us. This would be our compromise.”

It is a compromise that Kernes seems prepared to accept, despite everything he has suffered in the past year of political turmoil. Early on in the conflict with Russia, he admits that he flirted with ideas of separatism himself, and he fiercely resisted the revolution that brought Poroshenko’s government to power last winter. In one of its first decisions, that government even brought charges against Kernes for allegedly abducting, threatening and torturing supporters of the revolution in Kharkov. After that, recalls Zatulin, the mayor “simply chickened out.” Facing a long term in prison, Kernes accepted Ukraine’s new leaders and turned his back on the separatist cause, refusing to allow his city to hold a referendum on secession from Ukraine.

“And you know what I got for that,” Kernes says. “I got a bullet.” On April 28, while he was exercising near a city park, an unidentified sniper shot Kernes in the back with a high-caliber rifle. The bullet pierced his lung and shredded part of his liver, but it also seemed to shore up his bona fides as a supporter of Ukrainian unity. The state dropped its charges against him soon after, and he was able to return to his post.

It wasn’t the first time he made such an incredible comeback. In 2007, while he was serving as adviser to his friend and predecessor, Mikhail Dobkin, a video of them trying to film a campaign ad was leaked to the press. It contained such a hilarious mix of bumbling incompetence and backalley obscenity that both of their careers seemed sure to be over. Kernes not only survived that scandal but was elected mayor a few years later.

Now the fight over Ukraine’s federalization is shaping up to be his last. In late March, as he continued demanding more autonomy for Ukraine’s eastern regions, the state re-opened its case against him for alleged kidnapping and torture, which he has always denied. The charges, he says, are part of a campaign against all politicians in Ukraine who support the restoration of civil ties with Russia. “They don’t want to listen to reason,” he says.

But one way or another, the country will still have to let its eastern regions to do business with the enemy next door, “because that’s where the money is,” Kernes says. No matter how much aid Ukraine gets from the IMF and other Western backers, it will not be enough to keep the factories of Kharkov alive. “They’ll just be left to rot without our steady clients in Russia.” Never mind that those clients may have other plans for Ukraine in mind.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com