In the last year, policing has been the focus of more public attention than in any other time in recent memory. Cell phone cameras and social media have combined to draw unprecedented attention to controversial incidents, sparking national conversations about police training, culture, and the use of force.

There is anger on both sides of the debate, and for good reason. Communities are angry because they feel victimized by police abuses. It’s difficult for them to look past the shootings of unarmed black men like Tamir Rice, John Crawford, Levar Jones, and Walter Scott. Officers are angry because they feel attacked by a public that does not understand the job they do or appreciate how dangerous policing can be. It’s difficult for them to look past the shootings of officers like Bryon Dickson, Wenjuan Liu, Rafael Ramos, Alyn Beck, and Igor Soldo.

But while anger can motivate us to have important conversations, it becomes counterproductive when we allow it to dominate those discussions. Since last summer, the national debate on policing has been marked by rhetoric that, while heartfelt, risks fracturing, rather than healing, police-community relationships. Here are eight common misconceptions from both sides that aren’t just wrong, they are wrong in a way that undermines meaningful public dialogue.

1. Police officers are deliberately racist

Good officers take a great deal of pride in their professionalism, and professional policing requires responding to a person’s actions, not their race, gender, or other personal characteristics. For officers, accusations of racism are attacks on their professional identity and self-image. There are, unfortunately, officers who use racial epithets while out on the job, behind the closed doors, or on social media, and that should be dealt with swiftly and firmly. But conscious and deliberate racism is the exception, not the norm.

2. Racism is not a problem in policing

Even while conscious racism is rare, there are still two very real problems: systemic racism and implicit bias. Systemic racism refers to the way a system can create or contribute to racially discriminatory outcomes even when the individual actors within that system are not themselves deliberately racist. Consider the striking disparity in drug offender incarceration data from 2011: Although the total population was about 13.2% black and 77.7% non-Hispanic white, and although there were very similar rates of drug use among blacks (10%) and whites (8.7%), about 40.7% of state inmates convicted for drug offenses were black while only 29.9% were white. Why? Because impersonal factors within the criminal justice system—for example, how police agencies set their crime-fighting priorities, identify targets, and conduct investigations—systemically disfavor minorities.

Like nearly everyone else, officers are also affected by implicit bias. This unconscious bias can lead officers to perceive a black teen as more suspicious than a white teen or to find an affluent white woman more credible than a working class Hispanic man. These perceptions, in turn, can affect the officer’s decision-making and behavior in problematic ways.

3. There is a raging epidemic of police violence

Fueled by some truly disturbing videos of police violence, it is easy to believe that brutality is becoming increasingly common. But appearances are often deceiving. The human brain is wired to make judgments about the frequency of an event based in large part on our awareness of other similar, recent, and significant events. As a result of this “availability heuristic,” the number of recent, high-profile incidents of police violence can make it seem that police violence is far more common than it actually is.

So just how common is it? According to the most recent survey data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2008), officers used violence in about 1.4% of all civilian encounters, a percentage that has remained basically flat since at least 2002 and which represents a modest increase from the mid-1990s. On most of the occasions when officers did use force, they used relatively little: pushing, grabbing, and restraining are by far the most common types of police violence.

4. Police violence is so rare that it isn’t worth talking about.

The small percentage masks a large absolute number. Applying the 1.4% figure to the nearly 67 million police-civilian encounters in 2008, we’re left with about 938,000 instances of police violence. More troubling is the fact that the police used force almost three times as often in encounters with blacks (3.4%) as with whites (1.2%). And regardless of race, about three out of four of the civilians against whom force was used described it as “excessive.”

5. Police violence is acceptable as long as it is legally justified.

Officers often believe that the public should not criticize an officer whose use of force was legally justified. But the law is not a moral compass. The real question should be whether a use of force was avoidable (and thus, unnecessary), not whether it was merely lawful.

6. If suspects didn’t resist, officers wouldn’t use force.

Another common refrain is that suspects could avoid police violence by simply complying with officers’ commands. The first problem with this assertion is the number of the people who’ve had force used against them when they weren’t resisting or hadn’t been given time to comply. The second problem is that it is ultimately unsatisfying even for the incidents when a suspect does resist. This assertion relies solely on the answer to one question—“Was force authorized?”—without attempting to answer the more important follow-up question—“If it was, how much force was authorized?”

7. Police officers work in an increasingly violent and deadly environment.

Actual data simply do not support this oft-repeated assertion. The FBI’s data on Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted reflect a steady decrease in the number of officers feloniously killed over the last 30 years, and there has been no increase in either assaults or officer injuries. Our officers face very real risks which neither the public nor the officers themselves should ignore, but the law enforcement community loses credibility when it exaggerates those risks.

8. Officers who engage in misconduct are isolated “bad apples.”

Isolating problems by blaming individual officers fails to acknowledge systemic features that contribute to those problems. Organizational and cultural factors—that is, systemic factors such as institutional values, the supervisory environment, disciplinary mechanisms, and management practices—can set the stage for officer misconduct, from racist emails to excessive force.

Discussions about policing, both current practices and the future of the profession, are critically important. To elevate the dialogue, we all must think critically not only about each other’s positions, but also about our own.

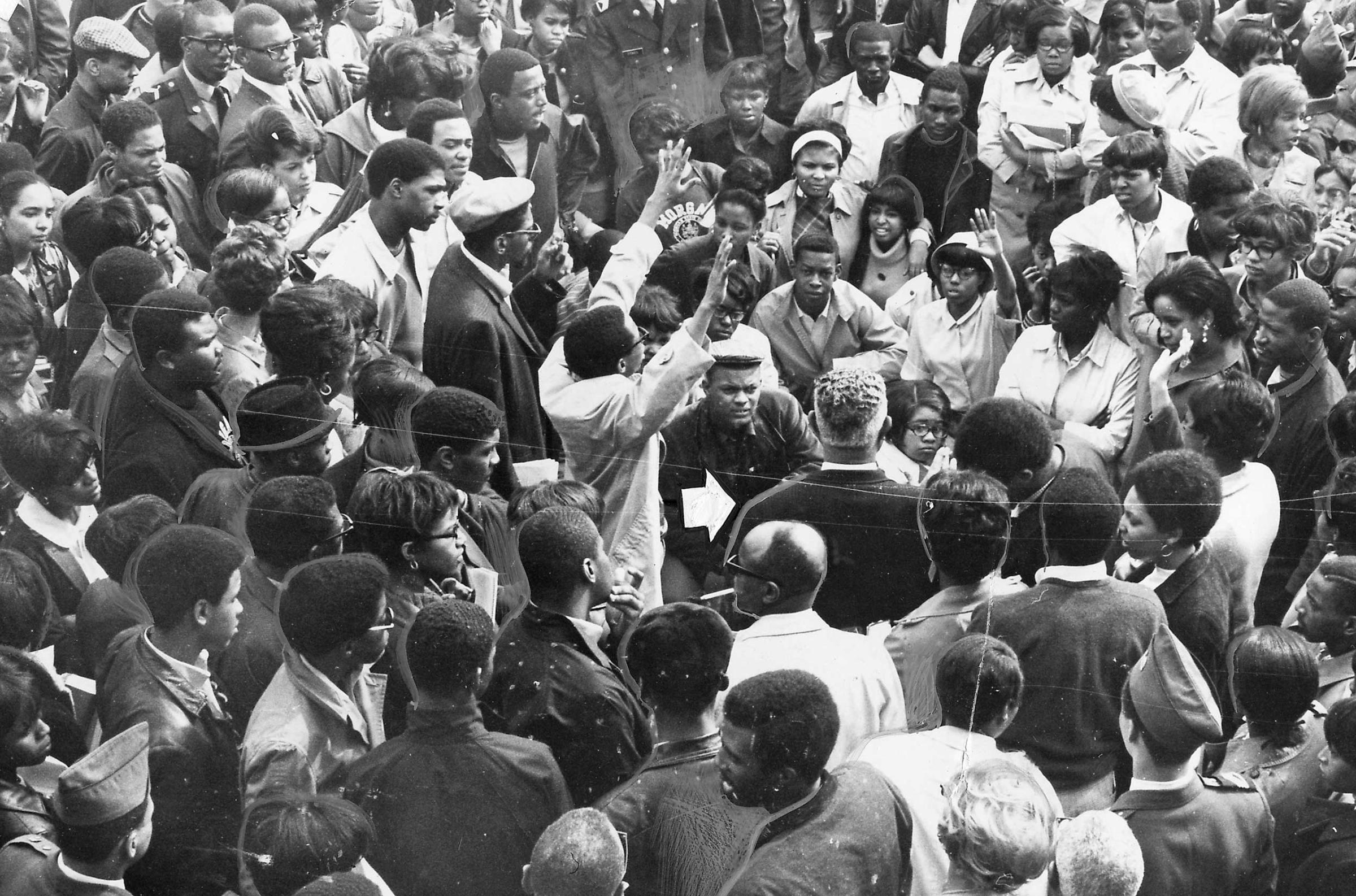

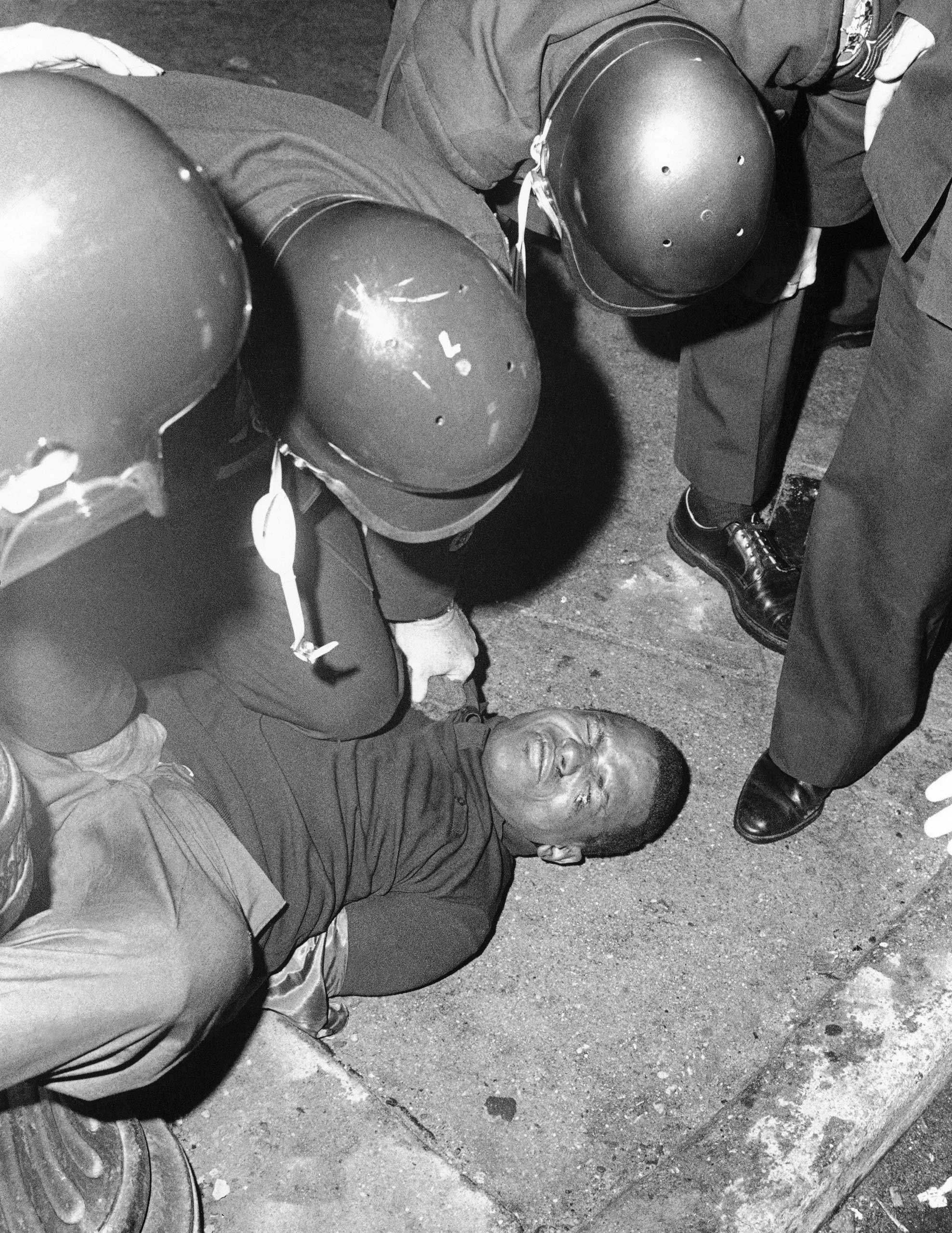

Baltimore Protests, Then and Now

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com