Despite his famous tendency to keep people waiting, Vladimir Putin arrived early on Wednesday at the latest round of negotiations to end the war in eastern Ukraine, and on Thursday he was also the first to emerge when they were over, looking pale and tired but, on the whole, rather satisfied with himself. “It was not the best night of my life,” the Russian president remarked with a smirk when he appeared before the news cameras in the capital of Belarus. “But the morning is good.”

For him it certainly was. Unlike his Ukrainian counterpart in these negotiations, Putin risked little going into these talks and even less coming out of them. The terms of the ceasefire agreement announced on Thursday were vague enough to seem meaningless on many of the key points of contention—even the central question of whether Russian troops are fighting in Ukraine or not was left undetermined—and as Putin was careful to stress while briefing the media afterward, he did not sign any kind of deal. That was left to Russia’s proxies in Ukraine, the separatist leaders that have been fighting for ten months against the Ukrainian military.

Meaningless or not, the terms of the deal appear to clearly favor the separatists. Under the agreement reached in Minsk, the rebel lines of supply from Russia will remain intact. Only at the end of this year would they even have to consider giving up control of the patches of border they control in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. As Putin was also careful to stress, the rebels would only have to relinquish control of that border when the government in Kiev grants the separatist territories sweeping autonomy, starts paying them pensions and other social benefits, plus the little matter of enshrining their “special status” of semi-independence in an amendment to the Ukrainian constitution. On top of all that, Thursday’s agreement grants legal immunity to anyone who joined the separatist militias, including the fighters responsible for killing Ukrainian soldiers and civilians.

The average citizen of Ukraine will likely find the terms of this deal humiliating, and blame will no doubt fall on President Petro Poroshenko, who sat opposite Putin in Minsk, when the time comes to implement it. Since taking office in June with a promise to make peace with Russia, Poroshenko has already faced attacks from political rivals and allies alike, as well as from protesters in the streets of Kiev, for ceding too much ground to the separatists. Now trying to change the constitution in order to appease more Russian demands will require a level of support in parliament that Poroshenko simply may not be able to muster. Pile onto that the requirement of welfare payments to the breakaway regions, and Poroshenko risks facing a popular revolt much like the one that vaulted him to power a year ago.

Poroshenko did not, however, come away with nothing on Thursday. The news of the deal, perhaps regardless of its substance, allowed the International Monetary Fund to move ahead with an additional aid package to Ukraine, which was announced right after the negotiations ended. “My sense is that someone was telling the Ukrainians that an IMF deal was contingent on a Minsk ceasefire deal,” said Timothy Ash, an economist at Standard Bank in London. “No ceasefire – no IMF deal.” Over the next four years, Ukraine now stands to get an additional $17.5 billion in Western financial support, which should be just enough to rescue its economy.

But even with that bright side to consider, Poroshenko wore a rather more dour expression than his Russian counterpart when he met the press. In his remarks, Poroshenko chose to emphasize the more immediate effects of the ceasefire agreement. All guns must go silent under the deal as of midnight on Sunday, Feb. 15, and all heavy artillery must be pulled back away from the front lines. All prisoners of war must be released or traded to the other side. All “illegal groups” must be disarmed, and all foreign fighters and mercenaries must leave Ukraine.

So what exactly counts as an illegal group in this context? And what is a mercenary or a foreign fighter? According to the Ukrainian authorities and their Western allies, Russia has illegally sent thousands of its soldiers to help the separatists fight the Ukrainian army. But Russia, for its part, denies that any of its soldiers are fighting in Ukraine, and Putin recently claimed that the Ukrainian military is in fact a “foreign legion” of Western personnel. So don’t expect the warring sides to agree any time soon on the definition of a foreign legionnaire or a mercenary in this conflict.

For Putin, though, that’s just as well. What matters to him is maintaining the perception that he is willing and able to compromise, and on that score the peace deal is already paying dividends. Hours after it was signed, the European Union was due to debate whether to impose another round of sanctions against Russia. But the E.U. foreign policy chief, Frederica Mogherini, announced beforehand that the sanctions issue had been taken off the agenda. Instead, the bloc would discuss how to use “all means at the E.U.’s disposal to facilitate the implementation of the agreements” reached in Minsk, she said.

Other European leaders seemed equally eager to take what they could get from Putin in Minsk. German Chancellor Angela Merkel called the agreement a “ray of hope,” while her Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier admitted that it was “certainly no breakthrough.”

But Merkel did not leave Minsk empty-handed. The talks, as well as her week of shuttle diplomacy to prepare for them, helped her to silence the chorus of Western diplomats and military officials who only a week ago were calling for the U.S. and Europe to arm Ukraine in its war against the separatists. While the new peace initiative gets a chance to run its course, the debate over arming Ukraine is sure to subside. That’s another reason for Putin to rest easy.

Read next: Here Are 7 of the Weirdest North Korean State Slogans

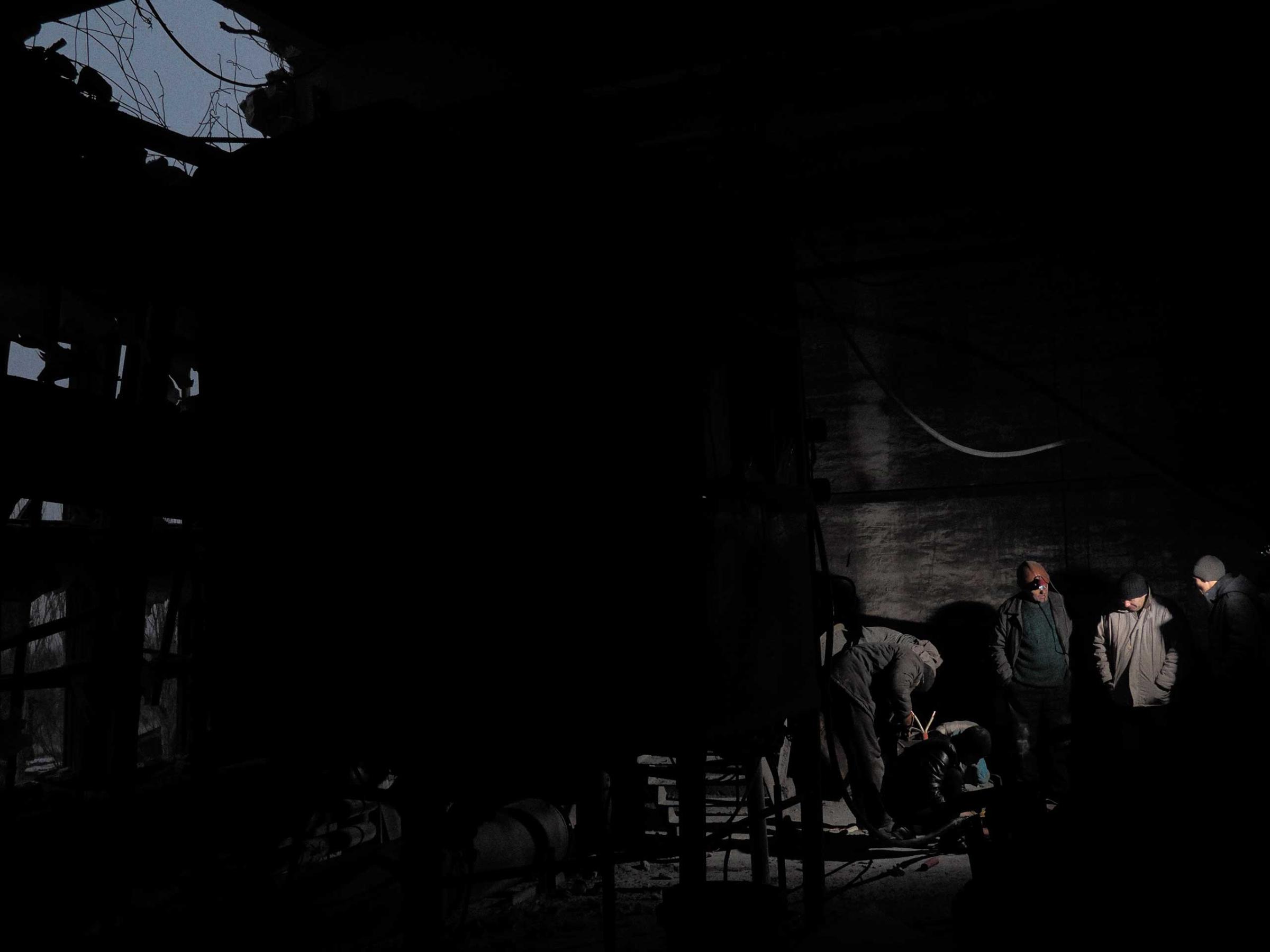

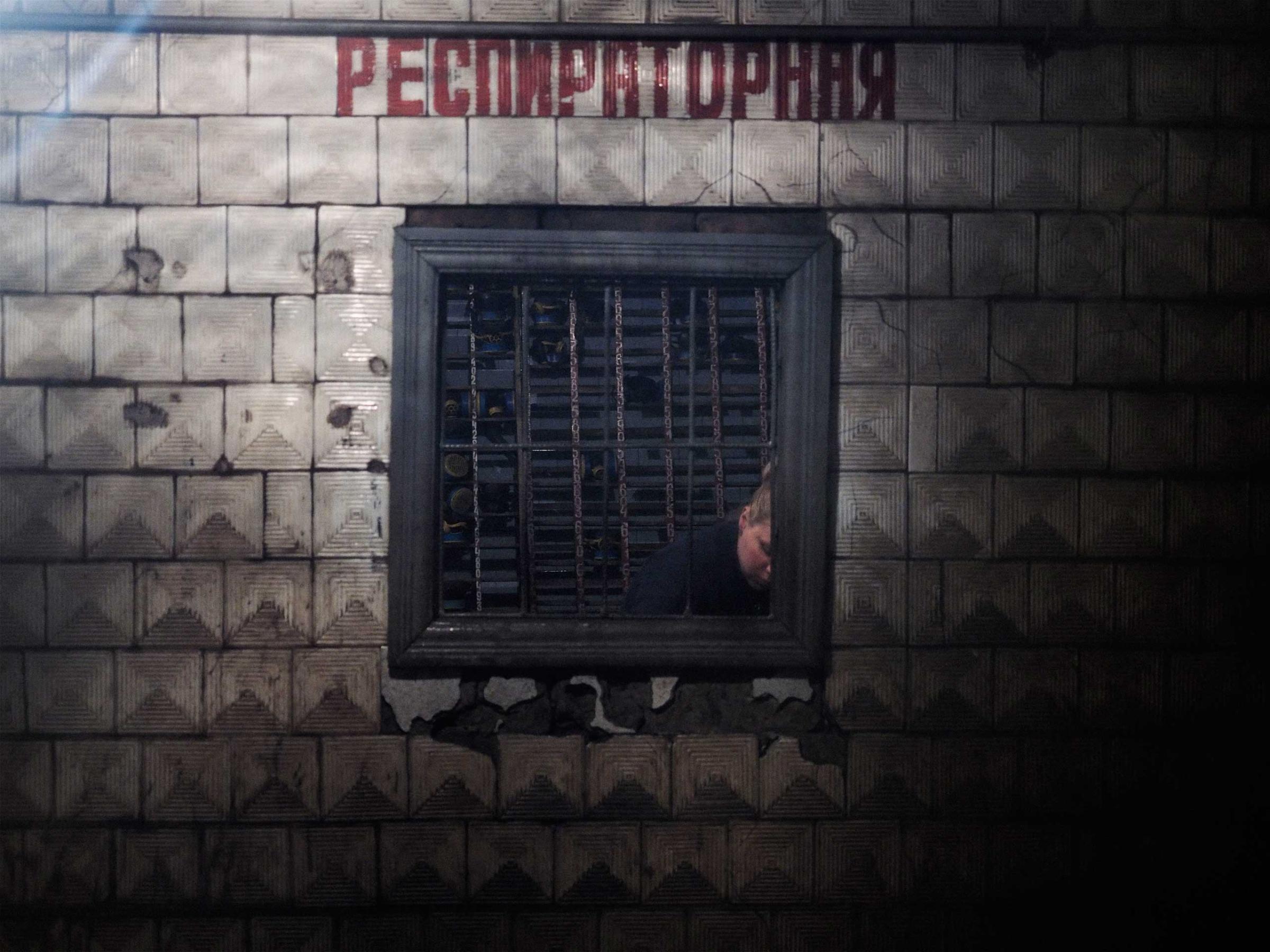

Beneath the Front Lines of the War in Eastern Ukraine

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com